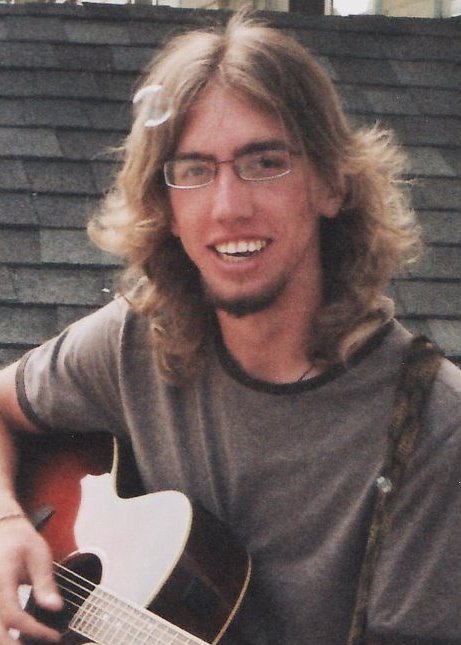

November 30, 2011: That time when I asked my son Jake to help me make some bars of soap.

I started by finding and collecting the supplies that we would need:

Molds: I decided to use the containers that Pringles chips come in as molds. They create a nice sized round disk shaped bar, and to get the molds all we had to do was buy some Pringles, eat them, and save the containers. Easy Peasy! Our family didn’t often buy chips, but this was a sacrifice we were all willing to make for soap.

Lye crystals were purchased in a local hardware store in a plastic jug.

Protective gear, because lye burns skin and eyes. It is an acid. Eyes, hands, breathing, arms & legs all needed protection. We poured the lye into water outside and though we planned to use a portable burner outside as well, we opted instead to just use the kitchen stove, so everything – all our supplies would be at hand.

Fat. For the recipe we would need 3 cups fat. I chose to use Crisco shortening because it is reltively cheap, food grade, and easy to work with.

Essential oils and mica colour (if desired, which we did not opt to colour our soap, we chose to only add essential oils).

A stick blender for whipping up the two distinct liquids into a saponified combination that will become soap.

This is what we did:

1.

Jake measured 3 cups Crisco shortening into an enamel pan while I measured 1.5 cups cold water into a glass bowl and also 1/4 cup plus 1 Tablespoon lye crystals into a glass cup.

2.

We set the stove burner on low heat to slowly melt the fat while Jake and I went outside to the picnic table with the lye crystals, a wooden spoon and the glass bowl of cold water.

Ever so slowly I poured the lye crystals into the cold water while Jacob stirred with the wooden spoon.

Even though there was no heat added by us, the chemical reaction between the lye and the water became very hot and there was toxic vapour which rose above the bowl.

3.

While Jake carefully stirred this witchy brew (it felt witchy because of the mysterious toxic vapour), I went inside and put away the jug of lye crystals, the lard container, and washed all the dirty dishes so far.

By the time things were cleaned up and the lye water was ready, the fat had melted. I turned off the heat under the oil.

4.

Jake carefully carried the lye water inside to the kitchen and then we waited for both the lye water and the melted Crisco to reach a slightly cooler temperature.

5.

While Jake stirred to melted lard very slowly, so as to create no waves, I slowly and carefully poured the lye water in and created no splash. The mixture turned orange, as it was supposed to. I washed out the bowl while Jake continued to stir.

6.

I got the stick blender out and began blending the mixture. It took about ten minutes before we reached what is called “trace”.

Trace is the stage where the lye water and the melted fat have emulsified to the point where they will no longer come apart. You can recognize it by using a kitchen utensil to write shapes in the surface of the soap liquid. If you can trace a shape and the shape stays visible for a little while. The soap liquid keeps thickening while you work with it.

Warning: If you are working with liquids that have gotten too cold too fast, trace might seem to occur much sooner than logical. This is called false trace. False trace will happen very quickly and the liquid might seem to be a bit grainy. There might even be solid chunks of soap in your mix. Just keep blending, true trace will come eventually. Higher temperatures prevent false trace, so don’t let your liquids cool too much before you start mixing them.

7.

Ten minutes was -for us- a long time to be using a stick blender, so we took turns to avoid arm fatigue. At one point, near the end, while Jake was holding the stick blender, I added 30 drops of our chosen essential oils to the mix. (This batch was ten drops each of patchouli, lemongrass and grapefruit. My next batch I used only lavender.)

8.

We poured the saponified soap liquid into our pringles containers and stood them up in the corner of the kitchen for four days while it hardened. Once the soap was hard enough, I unwrapped it from the pringles container and sliced the cylinders into round bars of soap. During this time, the lye is still active in the soap, so I had to wear protective gloves while handling it.

9.

Allowing for plenty of air flow, I stacked the round bars of soap like a loose wall of bricks out of the way on a towel. The soap needs to “cure” for another six weeks before it is both hard enough and safe enough to use.